Private Equity: Risk and Outlook

Private equity (PE) is acquiring ownership of—or a stake in—a company that is not publicly listed on an exchange. A typical PE firm will invest in a portfolio of companies to create a fund open to investors with the promise of future distributed returns. However, unlike shares traded on the stock market, PE firms cannot easily sell their stakes in private companies, meaning PE funds are comparatively illiquid and require a longer holding period. Alongside the substantial risks of acquiring companies and the aggressive use of debt to finance buyouts, PE firms present an interesting risk profile that warrants proportional risk management.

Private equity dynamics

PE firms raise capital through both equity (e.g., via external investors and internal revenue) and debt (e.g., through loans and bonds). The two main activities of PE firms tend to be venture capital, which involves early-stage/seed funding for companies with long-term potential, and buyouts, which involve the purchase of a controlling interest in a private company with the intention of improving the business, often using large amounts of leverage to acquire the company (hence the term leveraged buyouts, or LBOs).

In June 2023, Australian PE funds held roughly A\$66B in assets under management, or roughly 2.6% of Australia's GDP1. Most of these funds focus on LBOs, which typically have the following lifecycle:

- A PE firm acquires a company, often mostly through debt financing and a smaller portion through equity

- The PE firm attempts to improve the acquired business (or in poor economic conditions, simply wait for market conditions to improve), which can include streamlining operations to cut costs, financial restructuring and reshaping management, or selling off assets to pay down debt

- After roughly 5–7 years, the PE firm hopes to "exit" the opportunity by either selling the company (potentially to another PE firm, called a "secondary buyout"), or listing the company on an exchange via an initial public offering

In the case of LBOs, PE firms target companies that have strong monetary profiles (e.g., consistent yearly cash flows and recurring revenue), high margins, and a "moat," or differentiating factor. At the same time, PE firms try to identify undervalued businesses (companies that can be acquired for a lower price due to, e.g., macroeconomic factors) and businesses that have visible inefficiencies which can be ironed out to improve operations.

Risks in private equity

PE firms typically target returns of 20–25% (often calculated using the internal rate of return), but PE funds can be volatile and returns are not observed at a regular frequency. The salient risks in PE are:

- Market risk: Risk owing to external factors out of the PE firm's control. Changes in interest rates, recessions, and other unfavorable market conditions can lead to losses in PE firms' portfolios.

- Operational risk: Risk that PE firms fail to properly manage the companies they acquire.

- Financial risk: The aggressive use of debt financing to purchase private companies introduces the risk of defaulting on debt obligations.

- Liquidity risk: PE funds are inherently illiquid due to their investment in non-public assets. Liquidity risk can also extend to the acquired companies in the case of needing to meet short-term debt obligations.

As with most investments, these risks can be dampened—but not eradicated—by employing risk management strategies. Portfolio diversification can thwart market risk by spreading investments across a range of developing companies in different sectors. To mitigate operational risk, PE firms use fund management systems and ensure organizational structures such as boards and ongoing reporting functions are in place within acquired companies5. Due diligence is also a crucial review process prior to acquiring a company to avoid excessive illiquidity and financial risk.

Although PE funds are commonly understood to be riskier while offering higher returns, there is little academic consensus on their risk and return profiles. This is due to a lack of data, delays in receiving returns from an initial investment, challenging reporting of returns, the use of model-based valuations, and a potential volatility-dampening investment fee structure7. Quantitative metrics for risk of PE funds vary wildly, with estimates for beta spanning from 0.5 to over 2.56.

The consensus in the literature is that PE volatility (and beta) profiles can be understated, mostly due to "smoothed" quarterly returns of index providers7. Despite the illiquidity of PE funds, investors still expect quarterly performance results, meaning PE firms require methods to report ongoing returns. This is troublesome because PE funds hold investments for long time horizons at cost, with the true success of a fund unknown until the fund is wound down. Furthermore, model-based valuations of investments might not change much over time, which can understate funds' true volatility. This ultimately leads to smoothed returns that can paint an inaccurate picture of PE funds' riskiness.

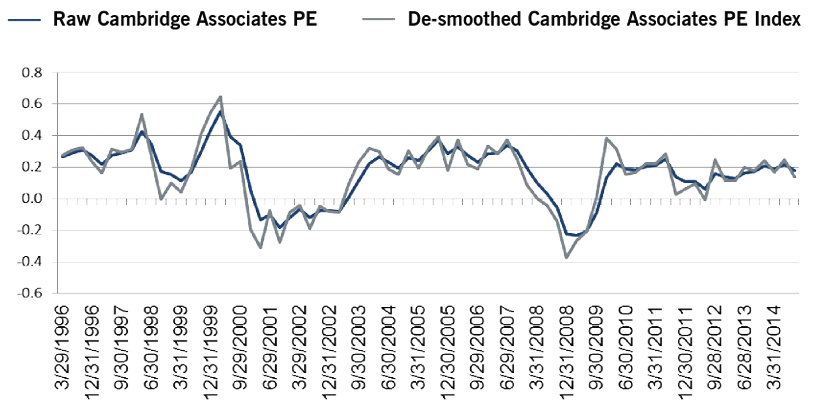

One approach to correct this type of reporting is to "de-smooth" returns:

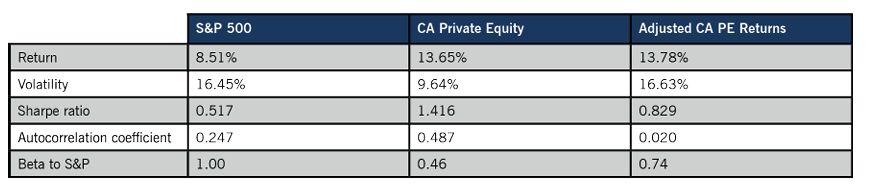

De-smoothed returns are calculated by applying statistical techniques to reported return streams. In the above example, the one-period autocorrelation coefficient is used to construct an adjusted return series9. The effect of this is substantial: Volatility in de-smoothed returns is 73% higher, leading to a 41% decrease in the Sharpe ratio. Interestingly, the beta (to the S&P 500) also increases under adjusted returns, suggesting an overstatement in diversification in non-adjusted returns.

Using de-smoothed returns is just one way of estimating the true performance of PE funds; other estimates including examining publicly-listed private equity funds and using industry and size sector ETF proxies, which have been shown to result in risk and return profiles comparable to de-smoothing methods7.

The outlook for private equity in 2025

Recent high interest rates and inflation have subdued PE borrowing, and consequently, activity. Uncertain market conditions may have also made PE firms hesitant to take mature businesses public due to lower valuations and subsequent returns. Despite the recent dip in global PE deal count over the past three years8, however, a 14% rebound in total worldwide PE deal value in 20243 may be a signal that PE activity is poised to ramp up in 2025, with investors eager to expedite an exit backlog of USD\$3.2T in global unrealized value from buyouts2.

The recent rate cut by the RBA and potential future cuts will lower the cost of borrowing for PE firms, opening up the possibility of new acquisitions through cheaper debt. However, Australian business conditions remain iffy: Despite an uptick in business confidence in Jan 20254, conditions have been weakening since late 2022, indicating robust demand but soft growth in the Australian economy. I'll be keeping an eye out for Bain's 2025 Global Private Equity Report scheduled to release in March.

References

-

Jacob Harris, Emma Chow (2024). The Private Equity Market in Australia (Bulletin April 2024, Australian Economy). Retrieved from Reserve Bank of Australia website: https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2024/apr/the-private-equity-market-in-australia.html ↩

-

Felix Barber, Michael Goold (2007). "The strategic secret of private equity." Harvard Business Review 85.9: 53. Available online: https://hbr.org/2007/09/the-strategic-secret-of-private-equity ↩

-

McKinsey & Company (2025). Global Private Markets Report 2025. Report. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/private-capital/our-insights/global-private-markets-report ↩

-

Michelle Shi, Gareth Spence (2025). NAB Monthly Business Survey Jan-25, NAB Economics. Retrieved from National Australia Bank website: https://business.nab.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/NAB-Monthly-Business-Survey-January-2025.pdf ↩

-

Ning Wang, Hongyu Zhang (2023). Risk Management Based on Private Equity Fund Investments. Modern Economics & Management Forum, 4(2), pp.34-36. ↩

-

Arthur Korteweg (2023). Risk and return in private equity. In Handbook of the economics of corporate finance (Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 343-418). North-Holland. ↩

-

Alexandra Coupe (2016). Assessing Risk of Private Equity—What’s the Proxy?. PAAMCO Perspectives. ↩↩↩

-

Bain and Company (2024), Global Private Equity Report 2024, Report. ↩

-

Philippe Jorion (2012). Risk management for alternative investments. Prepared for CAIA Supplementary Level II Book. ↩